Tags

colonial New York, culture, history, Manhattan, New York City, Schermerhorn Row, South Street Seaport, travel

Until the latter half of the 20th century, ships played a significant and historic role in the growth and development of New York City. Dutch ships during the colonial period moored around the “Great Dock”, whose approximate location would be today’s South Ferry. Small boats launched off the Great Dock to reach larger boats anchored offshore. Until the 1770s, the Great Dock was the only dock that projected out into the water. The area around the Seaport was a swampy wilderness situated a half-mile north of the original Dutch settlement.

1660 map indicating the Great Dock, which was situated on the southeast tip of New Amsterdam. The canal running through the middle of the colony eventually became Broad Street.

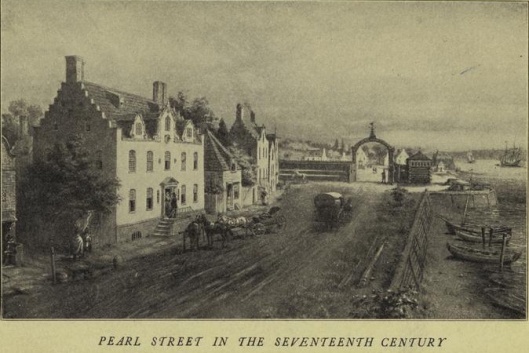

The Dutch soon began to use landfill to change the geography of lower Manhattan and by 1815, Water, Front, and South Streets were added to the map and extended well past Manhattan’s original shoreline along Pearl Street.

In 1784, the Empress of China, the first-ever American-built ship made of wood, set off from the South Street Seaport area in hopes of procuring imported tea and porcelain from China. The much-publicized event established the Seaport area as a focal point of international trade in the United States during the late 18th century. The US’ success in trading forged a new identity as a nation separate from its mother country of Great Britain. All trade conducted with China passed through New York before moving onto other ports such as Boston and Philadelphia.

1784 painting of the Empress of China. The ship was financed in Philadelphia and built in Baltimore before setting sail for China from the port of New York.

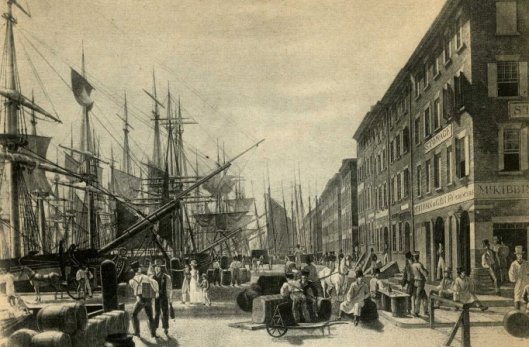

South Street Seaport was called “the port of New York” during its greatest period of success between the years 1815 and 1860, right before the Civil War. The advent of the ocean liner, a collection of ships that would cross the Atlantic on regular, fixed schedules contributed to the Seaport’s establishment as a major commercial port. Prior to the ocean liner, it was a rare event for ships to arrive and depart on schedule. Ocean liners such as the Black Ball Line, Red Star, and Blue Swallowtail began to sail between New York and Liverpool on set days, and South Street became the busiest port in America to receive goods from across America, Europe, and Asia.

Shipbuilding businesses, auction houses, and residences for seamen could be found in the four- and five-story brick buildings that began to appear along streets such as John, Fulton, and Beekman. The Seaport became even busier after clipper ships were invented; lighter, faster ships that carried large amounts of cargo became a necessity for the success of import companies. Shipbuilders rushed to build the biggest and fastest clippers to meet the demands of international trade, and New York soon developed a reputation for building beautiful, stalwart ships that could withstand the rough waters of long oceanic voyages. Soon the East River became a “street of ships” as piers lined both its Manhattan and Brooklyn shorelines.

The Seaport’s most famous buildings are lined up along Schermerhorn Row. Designed by Peter Augustus Schermerhorn in 1812 for use as “counting houses”, these brick buildings are some of the earliest forms of commercial building during the 19th century. Counting houses essentially were the finance and operations departments of various shipping and import companies.

As successful seamen and merchants moved away from the Seaport into presumably large and grander digs, businesses in the Seaport area began to diversify. By the mid-19th century, many of the counting houses’ ground floors became renovated storefronts; a grocer could be found at 2 Fulton Street and a boot-maker operated out of 12 Fulton. Both these buildings have been demolished.

This building at the corner of Schermerhorn Row was once a hotel whose guests included a fish dealer, a tug captain, and a poultry dealer. The smaller building to the left, 91 South Street, was a boarding house for workers of German and Swedish descent.

Labor shortages were rare as immigrants began to arrive en masse from Europe. The Seaport began its slow decline as iron and steel ships came to be favored over wooden ships, and buildings along places like Schermerhorn Row started to house boarders from a variety of backgrounds. 90 South Street, now long-gone, had records of residents who were longshoremen, mostly black.

New York’s shipping business eventually centered along the Hudson River during the early 20th century, and Seaport redevelopment began in earnest during the late 1960s. The South Street Seaport Museum was founded in 1967 to give New Yorkers and visitors alike a glimpse into the Seaport’s rich past. Schermerhorn Row was designated as a New York City landmark in 1968 and in the 1980s, South Street Seaport was born again as a shopping center and tourist attraction.

The Seaport is set to receive yet another major makeover. The Howard Hughes Corporation, current owners of the Seaport, have ambitious plans to tear down the three-level shopping center and build a structure that will house higher-end retail shops. Believing that local residents have largely shunned the naval-themed souvenir shops and chain establishments, city officials are hoping that these new development plans will help the Seaport and its surrounding neighborhood realize its full economic potential. Some locals fear these plans will change the Seaport into another Meatpacking District; developers are searching for anchor tenants along the lines of Saks Fifth Avenue. The new mall will also include a sprawling lawn and a theater with seating for as many as 700 people.

Will these plans change the flavor of the existing neighborhood? Most likely, yes. While no one can argue that the re-development of New York’s waterfront and proliferation of green spaces under the Bloomberg administration has improved the quality of life for many New Yorkers, we don’t need another Time Warner Center. We don’t need a downtown, hipper version of a shopping mecca like Saks. Living in Manhattan is already exorbitantly expensive and out-of-reach for many; proponents of the plan aren’t against big corporate chains, they’re against big corporate chains that don’t charge $300 or more for a pair of shoes and ultimately, bring in less tax revenue for a city that has become a playground and shopping mall for the wealthy.

The Meatpacking District today, all cleaned up with expensive, trendy boutiques and restaurants. Think Olsen twins. Will the Seaport have a similar fate?

I’m not against plans to breathe new life into the Seaport. What I am strongly advocating for is a plan to redevelop the Seaport into a recreational, entertainment, and shopping area that has a little something for everyone in New York City and preserves the Seaport’s storied past. I am content to let the past stay in the past, but seeing how “redevelopment” has often changed the character of various neighborhoods in New York City, any future plans for the Seaport should be more inclusive of the diverse needs and backgrounds of all New Yorkers.

I hope like-minded people will continue to converse and care about the evolution of this great city. Thank you for your efforts. I do miss the the flavors and quirks of nyc neighborhoods lost forever.

what a lovely post of past and present .

thank you

Thanks for reading!

I am a Schermerhorn and I think this is a fantastic representation of the growth of the shipping industry in NY. Haven’t been there yet, but hope I will be able to walk where my ancestors have. I think you have the right idea of it’s growth and agree it shouldn’t be just glitz. Good job!

Thanks for reading! I’ve always been curious about the descendants of these “First Families” of New York, so very nice to have one stop by the blog 🙂